by Katja Pitelina

As flutists, we have a repertoire of compositions spanning over 300 years, from the first publication of Michel de la Barre suites for flute and BC (1710) to the present day. If we take 1847 as the starting point for the existence of Theobald Bohm’s flute, the instrument played today, and call it the modern flute, we see that it has only existed for the last 176 years. It appears that a large chunk of beautiful flute music written during the Renaissance, Baroque, Classical and Romantic eras was not actually written for the flute we play this music today.

The flute is a beautiful and versatile instrument that has captivated audiences for thousands of years. Its history is rich and varied, and its construction and use have changes much over time, more then any other music instruments.

If we compare the flute and violin, we will see that over the past 350 years the violin has not changed its appearance. It used to have gut strings and now they are made from metal (of course I much simplify the matter now). For the flute it is a completely different story. Since the Renaissance, our instrument has been constantly undergoing mild or revolutionary changes in instrument design, aesthetics of sound production and performance style. Let’s run through the main types of the transverse flute history now.

The transverse flute dates back to Roman times (of which one bone specimen survives), but it falls into disuse in Europe before the 11th or 12th century. The medieval and renaissance instrument is simply a cylindrical wooden tube, plugged at one end, with a mouth hole and six finger holes.

The Renaissance flute came in three basic sizes which sometimes formed a consort, but the middle size, or tenor, was much more popular than the others and seems often to have been combined with other soft instruments. The bass flute is particularly awkward to play because of its wide finger stretch and the alto flute is a little shrill, so it’s not surprising that the tenor was preferred, even functioning regularly as the top part in ensembles. This use was made possible by the flute’s range of more than two octaves. The sound of the Renaissance flute is a little more airy or breathy than that of the recorder, but it blends well in ensemble and can be highly expressive.

The baroque flute (traverso, traversière) in D emerged toward the end of the 17th century, apparently the invention of the Hotteterre family of woodwind players/makers in Paris. It differs from the Renaissance flute in having a long, narrowing taper from the head joint to the foot and that helps to bring some of the harmonics better into tune. Unlike the typical Renaissance flute, it was also made in sections.

Initially, the Hotteterres made their instruments in three sections: a head joint containing the round mouth hole, a middle section containing most of the fingerholes, and a foot joint with the key for the last hole which raises the bottom note of the instrument by a semitone.The varieties of wood from which the flutes were made were boxwood and ebony with ivory decorations.

The flute in its new form became popular first in France, where it was well suited for the refined gestures and elegant ornaments of the French baroque style. The early, wide bore French instruments are best played in a significantly lower tessitura than renaissance flutes. They have beautifully expressive and mellow low octaves, and second octaves whose tone, while sweet, can be more penetrating (more soloistic) than that of the renaissance flute.

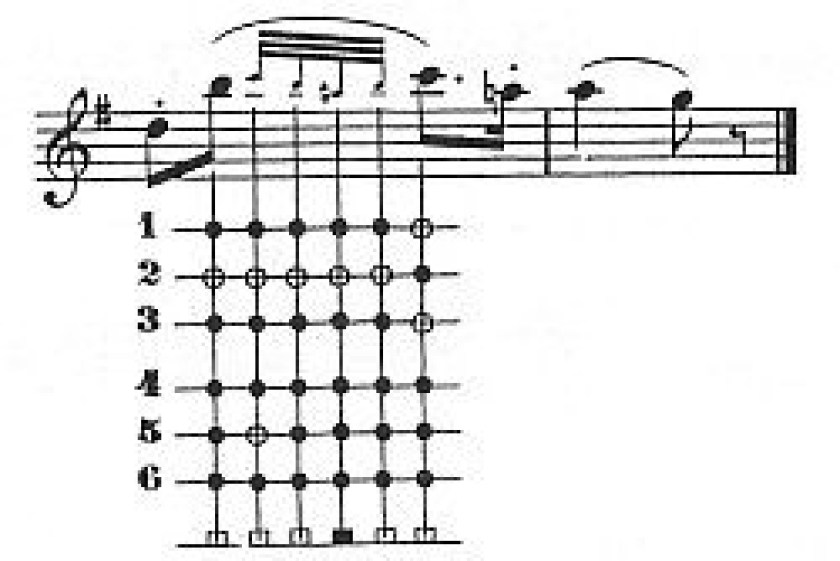

Indeed the music notation of the Renaissance times as wel as a early French baroque needs a special training and understanding, and looks very unfamiliar to the eyes of the modern flute players.

After the initial flurry of interest in France, German en Belgian makers began to produce instruments as well and the flute became so popular there that in England it was known as the German flute as opposed to the flute or common flute (recorder). These 18th-century instruments were typically made in four sections rather than three, with the middle fingerhole section being divided in two. The baroque flute possesses an extremely supple and flexible sound. It is capable of great nuances of dynamics and flips easily from one register to another, a characteristic that makes much baroque flute.

Starting circa 1720, many flutes were manufactured in four pieces. There were several reasons for this. Three piece flutes were still common in the 1720s, but were not fashionable after 1730 or so.

The four piece construction eased certain problems of manufacture and maintenance. It was easier to find stable and defect free pieces of wood when shorter pieces are required. And it is easier to get the tapered bore right, and to reream the bore in case of shrinkage, when working with shorter pieces.

But significantly, the four-piece construction also allowed for a corps de rechange. This term means that several interchangeable upper center joints were provided. They allowed the flute to be played at different pitches.

Original baroque and classical flutes were often provided with corp de rechange from three to seven interchangeable center joints. Usually the difference in length between consecutive joints was about 5mm. This makes a difference of about 5 Hz in the pitch. Note that the interchangable centers of the corp de rechange have tenons and not sockets at their ends. It would be more work to provide sockets on every center.

At first, the flute was associated primarily with sweet and soft sounds. In a 1702 letter comparing Italian and french music, François Raguenet wrote “…besides all the instruments that are common to us as well as the Italians, we have the hautboys, which by their sounds, equally mellow and piercing, have infinitely the advantage of the violins in all brisk, lively airs, and the flutes, which so many of our great artists have taught to groan after so moving a manner in our moanful airs, and sigh so amorously in those that are tender”. That is, oboes were good for lively music; flutes were good for tender music.

The tone quality varies mildly from note to note on a one-key flute. Notes like the low G sharp, for example, which must be produced by so-called ‘forked’ fingerings, have, like hand-stopped notes on a horn, a different quality from the neighboring notes. This is not unpleasant and adds color, rather like the variation in quality of a voice singing different vowels on different pitches. Trills on the baroque flute are lively. 18th century fingering charts consistently indicate a preference for trills with wide intervals over narrow ones. This is an important part of its character. This will change in 19th century in to the narrow and teasing trills.

The soft, veiled sounds of some notes, tendency to show different colours of the tones according to the character of the piece was broadly exploited by composers, but those characteristics were out of place when the composer or the player wanted a more uniform or aggressive tone. Additional keys were fitted to the one-key flute in the second half of the 18th century primarily to alleviate this unevenness, although two were also often added to extend the range downward. Six-keyed flutes appeared in England in the 1750’s. Mozart’s flute and harp concerto of 1778 was intended for such a flute, but additional keys were not common outside England until the very last years of the 18th century, and even then were far from universally accepted. As an example, the first flute teacher of Paris conservatoire was François Devienne who teached and played all his life on the one keyed simple system flute. Although during his life time already many different multi keys flute systems emerged and were played on. The characteristic shape of the mouthpiece on late baroque and classical flutes is oval.

One-key flutes were still being made and played circa 1900 and later. But these should never be called ‘baroque flutes’. Flutes made much after 1750 simply do not have the sound and playing qualities that make a baroque flute what it is.

Flutes from the second half of the 18th century and early 19th century (whether they were equipped with more than one key or not) often had slightly narrower bores than baroque flutes. Oval mouthpiece. Many flute makers made other subtle and not-so-subtle changes in the exact shape and taper of the bore, always striving to “improve” the flute according to the then current ideas and goals. In any case, the result of modifications in the bore and elsewhere in the design was that many of the classical flutes had easy high notes, including f”’, and up to a”’, and they could be very bright. A higher pitch contributed to the brightnessIt is difficult to describe in words this often bright sound of a classical flute, but in the best examples it is one of great charm. Of course, there was a gradual transition over time, and there is no sharp dividing line between baroque and early classical and late classical flute sound. My opinion is that English flutes circa 1800 retained more of the earlier 18th century sound ideal than did German flutes from that period, some of which are quite bright, and that the English flutes are not in general as easy to play in the highest part of the range (but there are exceptions).

Good flutes from the mid-18th century are very even and easy to play in tune. Some classical one-key flutes can be somewhat less even. It is dangerous to generalize, but on some (only some) late 18th century or early 19th century flutes, the forked fingerings for one or more of the first octave b’b, g’#;, and f’ can be less resonant than on earlier flutes, and may tend to be sharp. It can take a bit more “work” to get a good sonority from the first octave, but with work, they can be relatively loud on most notes. It may be that compromises were made in the first octave in order to get a smooth and easy playing third octave, which became more important. Flutes were routinely expected to play up to g”’, and the a”’ became common in symphonic parts in the 1790–1800 period. (But music for the amateur market was often restricted to e”’ and below in that period, as in the baroque era.)

In 19th century flute was a very popular instrument. Because of the sound and charm of the 19th century simple system instruments, defects and all.

There were also, of course, other reasons, including portability, lack of need for tuning strings or working with reeds, availability of low cost instruments, and, importantly, fashion. Those simple system flutes are not well understood today, even now that the baroque flute has come to be an instrument appreciated and studied by many flutists. One can also read that the pre-Boehm type of flute “clearly could not fulfil the requirements of the nineteenth century”. This is a modern conceit and to my opinion wrong one. The 19th century music can be played on simple system flutes. Though a simple system flute is certainly not the best tool for French music from the end of the century conceived for the silver flute, it can be the right tool for Wagner and Brahms.

Another thing not well understood is how the old flutes were played. Among other things, one must study and use the numerous alternate fingerings if certain passages are to be done smoothly.Alternate fingerings seem to be far more acceptable-sounding on the simple system than on a Boehm or other large-holed cylindrical flute. I am not sure why this is, although it is no doubt in part simply because the simple system flute is less tonally even to begin with, so additional inequality is not unpleasant. Modern taste forbids the regular use of “fake fingerings” on the Boehm flute, but alternate fingerings are an essential part of the technique on the old flute. Rockstro (1889), for example, gives 12 fingerings for f”’#. Fürstenau (1844) gives nine fingerings for c”’.

There is much that can be said about 19th century performance practices (articulation, slurs, dynamics, tempo, etc.) in general. Our interest is with the flute, and at this point we mention only a few effects that work well on, or which require, simple system flutes. Finger vibrato is the first thing that comes to mind. One can imagine that this has been used ever since there have been wind instruments with holes. It can be done to some extent even if ring keys or perforated keys are present, but works best with unencumbered open holes. This is a wavering of the tone caused by partially covering the sounding hole, or partially or completely covering and uncovering an open hole further down the tube. It was one of the favorite effects of Charles Nicholson; the English term was “vibration”. Finger vibrato can be controlled far more extensively than breath vibrato, both with regard to speed and intensity. Nicholson suggested a speeding up as the intensity diminishes, when time permits. It’s quite possible that if it wasn’t for Nicholson we wouldn’t be playing Boehm’s flute system right now.

Theobald Boehm (1794–1881) was a goldsmith, engineer, and musician (both performer and composer). He pursued and made contributions in all these fields. In the late 1820’s he (with Rudolph Greve) manufactured fine simple system instruments with eight or nine keys. About twenty years later (1847), we find him making all-metal flutes of a very different nature.The Boehm flute used today all over the world is in many ways the same instrument that was created in 1847 in Boehm’s Munich workshop. The net effect of his work was the overthrow of the design principles of the old flute (conical bore, closed-standing keys, six open holes under the fingers) and the institution of new, rational and logical principles (cylindrical bore with large holes in acoustically correct positions, open-standing keys, and a sophisticated mechanism), big amboushure hole and later lip plate. Inventing of the new system Boehm flute was another “revolutionary” point in history of the flute.

I think it’s important to remember that all the flutes I was talking about existed at a certain time and were entirely appropriate to the music, the time and the stylе. Also it is essential to see that changes and development of the flute still goes on. The instrument gets “tuned” for the needs of music written now.

In this regard, I cannot fail to mention The Kingma System® flutes which Eva Kingma, (dutch flute maker) has invented and further developed in collaboration with Bickford Brannen.

What makes this flute so unique is that, in addition to the standard Boehm mechanism, there are six extra keys. This is made possible through the use of the patented key-on-key system. These keys are used to produce six of the seven quartertones and multiphonic vents which are “missing” on the normal French model flute. The seventh “missing” quartertone is achieved by using the C# trill key together with the normal C key. The other five quartertones are produced by using the normal, open hole keys. This is a revolutionary system which provides the flautist with many extra possibilities.

I hope this short overview of the most important historical flutes tipes (not all of the existing models) will make you think and consider to play either Bach or Mozart or Beethoven or Schubert not the same way you would play Debussy or Nielson or Iber. Our inner sense of taste and the style for music comes from the understanding of the essential backgrounds. Nowadays we can listen all kinds of recordings of the flute repertoire. I think personally it is very important to develop your own performance skills and comprehension of the different music styles. And I believe that if we approach this matter from the understanding of the history of our instrument, we can get a better grasp on the stylistic performance details.

Katja Pitelina

The Hague 2023

Katja Pitelina

Website | Youtube

Residing in the Netherlands, Russian flutist Katja Pitelina is a skilled and versatile musician who creates beautiful concert programs, successfully combining both a modern and historically informed performance.

Katja’s expertise and dynamism is reflected in her remarkably broad repertoire encompassing music from 17th century Baroque to contemporary pieces – for each one she chooses the most appropriate flute from her personal collection of modern and period instruments.

In Holland and abroad, Katja regularly plays in concert series and festivals as a soloist, in chamber music ensembles, and with modern and baroque orchestras.

Articolo ricco di informazioni ed interessante per tutti i flautisti.

Congratulations, Katja!

Excellent article however I question the first photo of traverse Flutes. Louis Lot was only born in 1801, so could not have been making Flutes before that date?

Dear George, thank you for your comment, I refer there to the baroque flute maker Thomas L. Lot who came from a long line of woodwind-instrument makers native to the town of La Couture-Boussey in Normandyand operated businesses in Paris throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Luis Lot you had mentioned was descendants.

The La Barre edition of 1710 was far from the beginning of solo baroque flute music. The music that we have which was the earliest written are some Gaultier “Symphonies” published in 1707 but written quite a bit earlier as he had been dead for some time prior to that date. The Marais Pieces en Trio were published in 1682, La Barre Trios in 1694 and 1700. La Barre Pieces for flute and bass as well as duets had quite a few opus between 1700 and 1710.